|

November 2013

A Triptych in Remembrance on the Death

of JFK

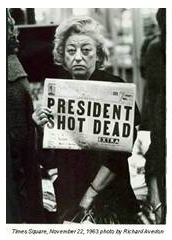

I. That Day

Shock and disbelief were the order of the

day. What could never happen here, happened here. The transference

of innocence to vulnerability, and that naïve comfort

of familiar terrain to a world turned upside down, took

but a nanosecond.

While it was not the only game changing

moment in our history—and the horror of 9/11 was still

four decades away— the assassination of President

John F. Kennedy had a singularity all its own. It was what

might be called, the First Great Tragedy of the Television

Age; an age whose potential had only been more fully realized

just three years prior, what with the first ever televised

Presidential debates.

Unlike December 7, 1941 of the previous

generation, “a date which will live in infamy,”

in which a military installation was attacked in a far off

place (exotic Hawaii not yet the 50th  state),

November 22, 1963 happened among our citizenry on our soil,

deep in the heart of Texas. It rained on our parade of invincibility;

bullets at a motorcade bearing the President in an open

car waving to the crowd. That’s what presidents did

back then. Where was the danger in that? state),

November 22, 1963 happened among our citizenry on our soil,

deep in the heart of Texas. It rained on our parade of invincibility;

bullets at a motorcade bearing the President in an open

car waving to the crowd. That’s what presidents did

back then. Where was the danger in that?

In a ’54 film entitled Suddenly,

Frank Sinatra starred as a would-be presidential assassin,

aiming his rifle through a telescopic sight from a hotel

window on an upper floor. But that was in the movies. Such

things could not happen in real life. In the ancient days

of Lincoln, yes, but these were modern times. Men were up

in space orbiting the earth.

Unlike Pearl Harbor, which lacked any ambiguity

and for which we would retaliate, then celebrate on V-J

Day, we never did “get even” so to speak, for

the assassination of JFK. The good never got to triumph

over evil. The truth never satisfactorily won out.

Fifty years later, conspiracy

theories still abound. Fidel is still alive, if one holds

belief in the Cuban-backed theory. And Lee Harvey Oswald,

shot and killed on live TV as if in a bad TV script, went

to the grave with a thousand unanswered questions. And soon

thereafter, assassinations and those attempted, would sadly

become commonplace.

So where were we on that day? Almost three-quarters

of us were not yet born. And when you weed out kids who

were ten years or younger back then, about one in seven

Americans now living, presumably remembers with some degree

of vividness, that day and the theater of events that would

unfold over that long weekend. We would sit transfixed before

our sets—first time ever for “24/7-news”

type coverage—for hours on end, culminating in the

funeral that Monday. “Regular programming” in

a realm of three TV networks, wouldn’t resume until

Tuesday.

I was a freshman at Manhattan College (two

years behind Rudy Giuliani) when first reports began to

spread on campus, that Kennedy and Vice President Johnson

had been shot. There were no readily accessible TV’s

in the vicinity, and so we relied on an ear here and there,

glued to a transistor radio, catching unclear or incorrect

messages (Johnson of course was not shot) which were relayed

to those of us clustered in the quadrangle as if in a third

world village awaiting word. These were what I have just

referred to as modern times?

Why was JFK in Dallas anyway? I didn’t

know. Nor was I aware back then, of the animosity that had

been brewing in Texas over his pending visit. My agenda

that Friday included placing bets in the cafeteria at lunch

for that weekend’s football games on “the ticket,”

a small time bookie sheet distributed by a classmate to

a dedicated clientele. And while Kennedy was the cat’s

pajamas at this all male Catholic college, I certainly wasn’t

following his doings as closely as the point spreads that

November. The high drama of his presidency had taken place

with the Cuban Missile Crisis in October of the previous

year. In comparison, this autumn was benign.

But it was now time to go to the next class.

And being the dutiful students we were, we went, though

as if sleepwalking through a bad dream. We were still unsure

as to whether Kennedy was alive or dead as we entered that

room. What happened then, is something I tried to capture

in a poem I wrote thirty-five years after the fact. Predominantly

in tercets and rhyme, it mimics a classic poetic construct

that we had been reading as part of the syllabus for that

course.

II. Greek and Latin Lit: 101

Upon entering the room, you simply said

in a manner of fact, “Yes it’s true. He’s

dead.”

And proceeded to go

on with that Friday’s class.

That part where Medea serves up the last

of her children chopped up on a plate

for Jason, his ravishing

appetite to sate.

And unsuspectingly he does.

And we knew just how vile a meal that was

on this day when the

classics were undermined

by Dallas: A Tragedy for Modern Time.

Our time. And you took it away;

the right to succumb

to grief kept it at bay.

You venomous, vainglorious man.

You served up Medea at a moment when

butchered progeny

was the last thing we needed.

With a smirk you watched as we sat defeated.

Was some point proved? Did we pass our test?

I’ve wondered

why we stayed bound to our desks.

Too civilized I suppose, to stomp out

of the room.

We should have sent you right to your doom;

trampled underfoot

and dragged across campus

as Achilles, passionate warrior that he

was,

had done with the carcass of Hector.

And now each time

at that vector,

that November day crossing of another

year,

I taste the irony in your name Mr. Lear.

And can only wish

you an afterlife fixed

to a barge floating down the river Styx

winding its way through the sewers of Dallas

encircling the sins

of fraud and malice.

And each time in passing pray you are

sprayed

with the brains that flew from that motorcade.

In response to my

whereabouts that day, I tell

how you taught us,

you bastard, the classics so well.

—Ron

Vazzano

III. While Jack As Ever…

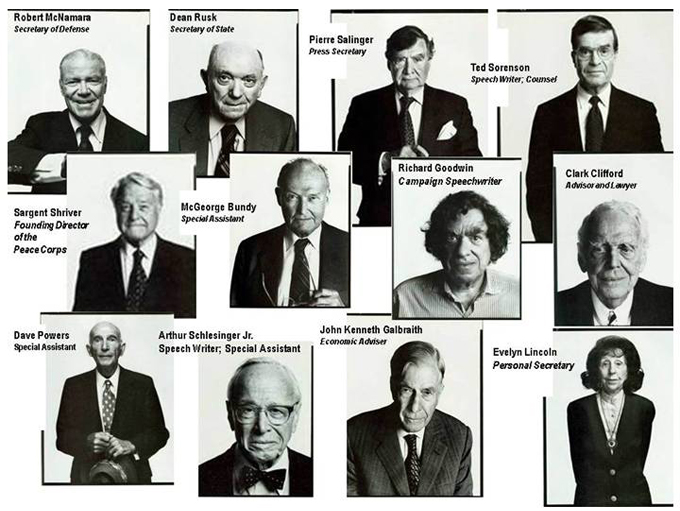

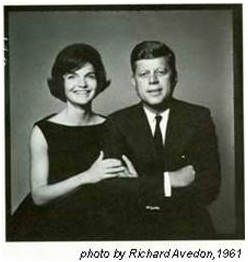

Thirty years following Kennedy’s assassination,

famed photographer Richard Avedon sought out many of the

knights and squires who had so diligently served in those

so called days of Camelot. This resulted in rather stark

portraitures which he had taken over a two month period

leading up to a photo-essay that The New Yorker

would publish that October of 1993. It was entitled “Exiles:

The Kennedy Court at the End of the American Century.”

When I got to meet Avedon at a private book launching party

later that year— for what has become a gargantuan

coffee table classic, An Autobiography Richard Avedon

(October,

2004 Newsletter)— I discussed the “Exiles”

project with him. In revealing some back-stories of the

photo shoots for it, his comments like his photos, were

unsparing. (On Ted Kennedy, who sat for him, though not

appearing in “Exiles”… “He looks

like shit.”).

Inspired by this work, which invariably takes one back to

associations with that fateful November day, I had written

a poem which I just happened to have on my person (do we

not all have an agenda?). Upon hearing of this, as I described

it at the time, “he reacted like a schoolboy, as he

gleefully tucked the poem away in his jacket pocket for

reading at some time after the party’s conclusion.”

With an Avedon epigraph and selected photos from “Exiles,”

the poem follows.

While Jack As Ever

I traveled across

the country to photograph surviving men and women

of that period—people mostly of my generation,

who for a while had faith in power.

—Richard

Avedon

Eyes gone to glass; eyebrows all askew

in odd elfin configurations.

Some try on a smile. Others?

Their faces reassemble for the clarion’s last

call.

And it turns on them like rotting fruit.

Where were you when you heard? The

years—

The Grand Inquisitor. The question? Always.

Even when not asked. But the years can only

be blamed for that which makes you

at one with the liver spots.

Some of you, if nothing else,

might have managed to wear the right tie.

The motorcade, The Calling,

were once that of pin-striped precision—

a carrousel from which you seized

the brass ring that was your day.

And it seemed as if it just went

by

reflected in your high-glossed hair

heralding the Camelot colors.

Yet all they can muster, these mere

pastels

of their once shining selves,

through the bars of this cruel cage of irony:

a stare. The salt still in the wound.

While Jack as ever… the handsome

prince.

—Ron

Vazzano

PPS

With the exception of Richard Goodwin, who

is married to historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, all of the

Camelot players pictured above are gone. As is Avedon.

¤

In the current November

issue of Vanity Fair, cultural critic James Wolcott

has written an excellent piece, “Chronicle of a Death

Retold,” that Kennedy lovers and haters should find

compelling. The thrust of it can best be summarized by this

excerpt set beneath its title:

The

avalanche of books marking the 50th

anniversary of J.F.K.’s assassination is both too

much and not enough. The inexplicable loss,

the unanswerable questions, the sense of history

suspended—they’re all still being fed by

the powerful charisma of the man who was

America’s first Pop president.

***

Picture a Palindrome: #5

—Ron

Vazzano

***

To Invite the Redskins

Over for Thanksgiving?

With Thanksgiving coming up,

and given its colorful origin of Anglican folk and Native

Americans making nice in the autumn of 1621, I had been thinking

of having the Redskins over for dinner. Oh, but that name.

I don’t know how you dance around it, but it is rather

racist. Washington Redskins? Something tells me, you would

never have teams called the Washington Whiteys, the Detroit

Darkies or the Seattle Slant-eyes.

Another garden variety appeal for political

correctness? Or is there something more here in this case?

I think the latter.

Some things just cross over the fifty-yard

line, and the Washington Redskins have. And so yes, once again,

many are calling for a penalty flag on the play in the form

of a name change. Even the President has chimed in on the

matter: "I don't know whether our attachment to a particular

name should override the real legitimate concerns that people

have about these things."

A recent poll showed that a majority of Native Americans find

“Redskins” offensive. Another poll showed that

fans of the team, even if against changing the name, would

still continue to root for it if they were called something

else. And there is precedent for taking that sort of action,

as did high-profile St. John’s University following

the ‘94-95 school year. Stuck with a double whammy of

suggesting both race and gender bias in their “Redmen”

nickname—stretched across 16 varsity athletic programs—they

changed it. No, not to the “Neutralcolorpeople,”

but to the Red Storm. And the fans still followed. And life

went on.

Anyway, if I do invite the Washington Name

Pending, I’ve got to invite all those other Native American

associated teams as well, no? With their questionable names

and/or logos and all? Take the Cleveland Indians’ red-faced

Chief Wahoo. Please. And is being called Brave or Warrior,

a compliment or a racially driven stereotype? And yet in the

spirit of that 1621 Thanksgiving, would it not be fitting

to have them all at the table?

Though what was that spirit really about? And what did actually

occur? And who was there? And how were they able to communicate?

And so on and so forth. Just some of the questions one might

ask, before planning such a gathering.

Of course Wikipedia, whose virtues are extolled

by Nicholson Baker in this month’s Quote of the

Month, provides some answers. In the department of perhaps,

“Too Much Information” …

“The

event that Americans commonly call the ‘First Thanksgiving’

was celebrated by the Pilgrims…at the Plymouth Plantation…

after their first harvest in the New World in 1621.”

“New

England colonists were accustomed to regularly celebrating

"thanksgivings"— days of prayer thanking

God for blessings such as military victory or the end

of a drought.”

“This

feast lasted three days, and was attended by about 53

Pilgrims and 90 American Indians… they went out

and killed five deer…’ "

No turkeys?

“Squanto…who

resided with the Wampanoag tribe, taught the Pilgrims

how to catch eel and grow corn and served as an interpreter

for them (Squanto had learned English during travels in

England).“

“Additionally,

the Wampanoag, Massasoit had donated food stores to the

fledgling colony during the first winter when supplies

brought from England were insufficient.”

One big happy family? Well, maybe not exactly.

As with the controversies over names and logos, the very celebration

of Thanksgiving itself has also been called into question

in some quarters.

“Since

1970, United American Indians of New England

have gathered on Thanksgiving Day at…Plymouth Rock,

to commemorate a ‘National Day of Mourning.’”

According

to the protesters…“The traditional narrative

paints a deceptively sunny portrait of relations between

the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag people, masking the long

and bloody history of conflict between Native Americans

and European settlers that resulted in the deaths of millions.”

Maybe I should just go back to the Thanksgiving

Day raison d'être, as proclaimed by the Father of Our

Country, in the first nation-wide celebration in America on

November 26, 1789:

"…a

day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by

acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal

favours of Almighty God.”

While visions of Rockwell dance in my head.

Yes, of course. George Washington said it—

God and all; Norman Rockwell painted it— family and

all. That’s the ticket. Who could find fault with any

of that? No names. No logos. No problems. Sorry guys, maybe

next year.

***

Quote of the Month

“Wikipedia is just an incredible thing.

It’s fact-encirclingly huge, and it’s idiosyncratic,

careful, messy, fun, shocking, and full of simmering controversies—and

it’s free, and it’s fast. In a few seconds you

can look up, for instance, ‘Diogenes of Sinope,’

or ‘turnip,’ or ‘Crazy Eddie,’ or

‘Bagoas,’ or ‘quadratic formula,’

or ‘Bristol Beaufighter,’ or ‘squeegee,’

or ‘Sanford B. Dole,’ and you’ll have

knowledge you didn’t have before. It’s like

some vast aerial city with people walking briskly to and

fro on catwalks, carrying picnic baskets full of nutritious

snacks.”

—Nicholson

Baker

The

Way the World Works

***

fini

|